Quick links: my home page • my blog • Choosing My Confessions

Those early days sitting in the water and watching the horizon and looking backwards to the edge of the island and wondering about the space in the water . . .

*

Almost one whole wall of Chris’s studio is a big wooden door that opens to the east, to the first morning light, and a view of a lawn, some small trees, the road below, and a forested ridge above. Another wall is covered by two huge drawings, from a series he worked on a few years ago. The third wall is lined with untidy bookcases, disgorging art books and catalogues, and dusty hardbound volumes of classic West Indian novels discarded by a library in Port of Spain, their spines still tattooed with Dewey decimal call-letters. On the fourth wall, dozens of evenly spaced pushpins make a sort of grid. Sometimes the grid is filled with small drawings hanging from clips. Sometimes the wall is mostly empty.

A big table sits right across the doorway. There is a strong lamp suspended above, and a tall stool pulled up alongside. On the table there are bottles of ink, tubes of paint, jars of brushes; a telephone, scraps of paper with phone numbers, names, lists; a bowl of coins from many countries, a row of ornate old-fashioned soft-drink bottles—Solo, Ju-C—and all sorts of odds and ends and strange objects, some of which may be artworks or fragments of artworks; and, on the only patch of clear surface, a stack of paper six or seven inches high.

Apart from the tall stool near the table, there are three old kitchen chairs, which came from Chris’s parents’ house in Diego Martin. There are boxes in the corners, some labelled (“Unsorted Mail”), some anonymous. There are small shoals of CDs, bits of discarded clothing—a purple sock—and what look like scraps of lumber. There are paintings and drawings in frames, stacked facing the walls. There are children’s toys, strayed from the rooms of the house above.

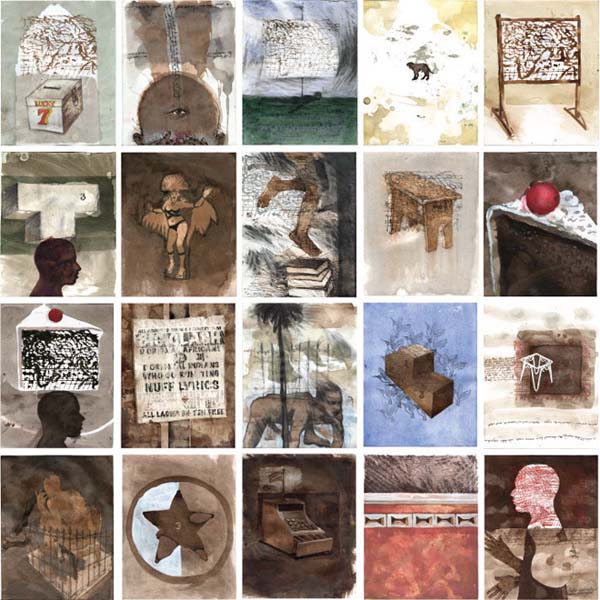

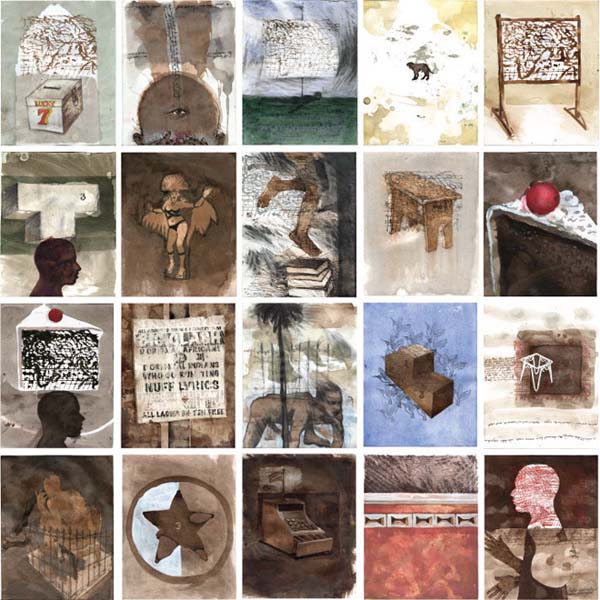

Several times over the last year I’ve visited the studio to look at the ongoing series of drawings Chris calls Tropical Night. Sometimes the drawings—each about nine by seven inches, on thick paper—have filled the pushpin wall. Sometimes they are stacked on the table or stool.

Say seven by seven by nine inches, the stack of paper: a solid object. It has real weight. It casts a shadow. Chris talks about exhibiting the drawings like this: piled up, face down. The longer I stare at the stack, the more it looks like a piece of minimalist sculpture, a cuboid with ridged edges stained with brown ink.

When the time comes for me to leaf through the drawings, Chris usually finds a reason to leave the studio. I turn the drawings over like pages in a book. Each time, the order has changed. Human figures, maps, birds, the sea, walls, benches, limbs, numbers. Some of the drawings have become familiar. Some are variations on ones I’ve seen before. Some are entirely new. The new drawings shift the narrative, as it were; I thought I’d put a story together, but now there are fresh meanders in the stream of consciousness. I don’t, after all, know where this is going.

*

“It feels like saying something twice, or again the following day in another conversation, and realising some connection or what the idea was really about.”

*

I am sitting in one of the kitchen chairs in the studio, sipping from a cup of milky coffee, staring at the pushpin grid on the wall in front of me, and listening to Chris. Words spiral and spool, as he plucks anecdotes from his capacious memory, pinches together recollections and observations and insights, facts from yesterday’s newspaper with fifteen-year-old gossip.

One of Chris’s favourite words is “conversation”. He uses it in every third or fourth sentence. But in my conversations with him I find I mostly listen. Partly because I’m caught up in the swirl of his words and ideas, and don’t want to interrupt. Partly because his intense and effortless verbalness leaves me feeling wordless. Images are supposed to be his medium, words mine. So why does he find it so easy to spin his phrases and lyrics, why do my own sentences feel like knots of barbed wire in my throat?

*

The writer, like the artist, works in a small room crowded with strange objects. He sits at a low, square table, painted brown. The table faces a window.

It is early morning, and the light is still soft. The writer, like the artist, sits and stares at the sheet of paper before him: empty, white. In his hand he holds a pen.

Making ink-marks on a sheet of paper: that, it has been said before, is what artists and writers have in common. But this morning the writer does not know where to start; or, rather, how.

In his hand, the very slight weight of the pen—Sanford Uni-Ball Onyx, fine point, blue ink—is a gesture both familiar and strange. The pen is both a comfort and a taunt. And the empty, white sheet of paper is a prism through which the writer peers into a dark-filled, light-filled space that, this morning, looks completely empty.

*

“I like to draw. Drawing is my handwriting, and my thought process.

“I often use the word ‘note-taking’—note-taking to me is conceptually very important. It’s a process of investigation, of speculation, of questioning. It has to do with notions of being sure and notions of being unsure. There’s a kind of instantaneity in that moment of reverie, of thinking. That’s the free space I’ve created for myself. But at the same time, the fact that these are just simple thoughts on simple pieces of paper means that to be speculative isn’t weakness. Speculative is openness. It’s a domain of possibility.

“When I make those marks, there’s a sense of being alive.”

*

The iron fence of a now-demolished colonial mansion, its palings sprouting fleur-de-lis finials. An athlete’s podium, its one-two-three steps irrefutably defining degrees of victory. A cash register with empty drawer lewdly gaping. Women in white high-heeled shoes. Men peering over walls. A man embracing nothing, embracing an empty space where something should be, the exact shape of another body. Tufts of bright green grass springing from the blackened earth of a burned hill.

Who is inside? Who is outside? Who is stepping out, or up? Who is stumbling in, or down? What happens next?

*

—Something’s worrying you about these drawings.

—Yes.

—What?

—The same thing that worries me about these notes I’m trying to write. It’s the matter of having to explain. To elucidate.

—To elucidate is to “make clear”….

—But “making clear” is the opposite of what the drawings seem to do—the prevailing murky browns and greys are like a tonal metaphor. But I also mean something else. Something like what Chris means when he asks if the work has “readability on its own merit”.

—The burden of narrative?

—No. What you might call the burden of context. The burden of history. The burden of being from a place—it’s tiresome to keep saying this, but even more tiresome that it’s true—from a small, peripheral place where individual sensibility is trapped on all sides: by ideologies, by national “culture” narratives, by stereotypes—by that whole tangle of expectations about what it means to be an artist from and in the Caribbean.

—But the subject matter of the drawings is unavoidably “from and in the Caribbean”—it’s the sometimes mundane, sometimes crazy everyday of an individual living in Port of Spain and immersed in all the elements of life in the twenty-first-century urban Caribbean—all those elements processed into what you’ve described as a visual stream of consciousness….

—Yes, but must the elements of that stream, that consciousness, be annotated for an audience outside that twenty-first-century urban Caribbean context? And in the absence of such annotations (which I’m not interested in providing), can that audience—will they—respond to lines, shapes, colours, tones, the immediate sensation, the “brown”, the mood, the mystery?

—And your notes?

—Don’t explain anything. Don’t come to any conclusion. Merely describe my own hesitant, indecisive experience of the drawings—looking at them, puzzling over them, talking to Chris about them.

—And you worry….

—Whether that is enough. Whether the notes themselves have any “readability”. If I had any talent for fiction I would write a short story instead.

*

“There are narrative passages. There are moments when I see a path, and I try to run it down.” But: “Sometimes I don’t want to prescribe the reading.”

The reading. That is my urge: to “read” these images, like a story, like a book.

Maybe it’s the “bookness” of the stack of drawings, sitting there like an unbound novel, with the patience of a book. (A book will wait five hundred years, then a reader opens it and the words unfurl fresh as flowers.)

Maybe it’s the lines of text, in Chris’s ornate scrawl, that embroider the drawings, not naming or explaining, but reaching, it seems, for their own plotlines.

Maybe it’s the many hours I’ve spent talking with Chris, or listening to him—maybe they’ve convinced me that he has something like the sensibility of a novelist, taking in and storing away every detail, penetrating into the deep psychology of things and places and people. A poet’s instinct is to pare away, a novelist’s is to pile up, pack in, fill the room of the imagination with as much furniture, as much equipment, as much apparatus as possible.

Or maybe the “book” I’m trying to read is a reference work: a dictionary, or an encyclopedia, scrutinising the world, imagining its complexities into small constituent fragments, holding each fragment up to the light, describing it from many angles, enquiring after its pronunciation, its derivation, its possible and impossible uses.

I look up and for a moment it seems the images in the drawings have taken three-dimensional form and are populating the studio. Near-invisible lines of trajectory connect object to object, and object to image on the pages in my hands. I am caught in this web, and the whole room is washed in sepia ink.

I close the “book”.

My eyes readjust and once again I see chairs, bottles, boxes, scraps of wood.

The stack of paper sits on the only patch of clear surface on the table, jostled by jars of brushes.

I am thinking: Do these drawings “rhyme”? Do they have a “rhythm”?

*

Searching for sweetness in the darkness across the sea

*

“The texts on the drawings are written free-form. Sometimes there’s spelling mistakes, grammatical mistakes, and things repeat, because the idea is a kind of associative writing, a rambling, that I then place in the context of the drawings.

“I’m never sure if they’re explanatory, or if they’re sort of parallel.”

*

I realise that the drawings cast into clearer relief a certain literary quality of Chris’s entire oeuvre. I don’t mean just that he’s a practising critic. I don’t mean just that his works on paper, even at their most cryptic, almost always have a strong sense of narrative. I don’t mean just that his groundbreaking early work, Conversations with a Shirt Jac, was in effect a soliloquy; or that his sound installations seem to play with elements of performance poetry; or that text—actual writing, the physical shapes of words—recurs through his drawings. I mean—and I’m trying to understand—something about his mode of thought, the way Chris experiences and understands the world. His mode of thought seems essentially that of a writer. He has what I think of as a writer’s intense self-consciousness, a writer’s obsession with translating the world into words to keep the world from disappearing (as it ultimately must). Drawing is his note-taking, he says, but I suspect he also has that voice in his head that never stops detailing and describing, converting sensory facts into words and those words into sentences, so that each day is an epic novel of the mundane that will never get written, and memory is a series of inaccurately recalled quotations, and these drawings are snapshots from a stream of consciousness, from an unresolved state of being.

An autobiography composed from metaphors.

A visual dream-diary. Of waking dreams.

*

There is a kind of bibliophile’s parlour game in which you arrange books on a shelf so that the sequence of titles on their spines tells a story.

You might do something similar with the titles of the individual drawings in the Tropical Night series.

Feathered Bat Descending. In the Dance. Hop Skip Jump. Jump Up. Shot Call. Flight.

Coming and Going. Immersed in Explanations. Submerged.

Oxford Journey. Castaway. New World. Making Progress.

A Next Day. Sitting Here Watching. Open Seas. Day In, Day Out.

After the Fire. Crown. Thorns. Bird Stress. Air. The Hills. That Tree. The Hunger.

Another kind of narrative. Another way, perhaps, of not seeing the thing at hand, the marks on the piece of paper before me.

*

“The word ‘literary’ could imply or require a narrative pursuit, and that may limit me or demand a purpose or some kind of accountability. I do not really want to have a way through this, or an idea of a way. I feel adrift, a bit lost, and I am looking for and at signs. I do not want to frustrate the viewer. I am searching for empathy.”

*

A white wall covered with a grid of evenly spaced pushpins is a map waiting to be drawn.

A blank sheet of paper is an airless room waiting for a conversation to start.

*

When Chris first gave me scans of some of the drawings, I put them in a folder on my desktop called “Brown Drawings”. Maybe he used this term casually in some early conversation. Maybe it was the first thing that came to mind when I made the folder, more than a year ago—the label that my semi-conscious mind grabbed at to distinguish these from his earlier work.

Many of the drawings are literally “brown”, composed largely in washes of sepia ink. Some are not. This is obvious. This is the artist’s prerogative of medium. It is also obvious that the “brown” is, more meaningfully, a mood. The dark brown of dried blood—

—or the weary brown of an old photograph, but not the kind of photo that inspires nostalgia, like an old black-and-white snapshot of a Carnival costume from the 60s or 70s, and looking at it you feel the dust and hot sun of that moment, the weight of the costume and the stickiness and the head-pounding noise, and you’re glad you’re not there; it might even be a moment from your own past that you’re glad you don’t have to relive. Or just a meteorological brown—

—a tone of spirit familiar to anyone who grew up in the tropics, a brown found only in this climate, like a film of dust over the bright blues and greens and yellows that are supposed to be the exemplary colours of the tropical landscape; the gloom of that “shadowed space that is not between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. with intermittent clouds.”

The murky brown of a situation or a frame of mind when the silt of too many memories and expectations leaves your thoughts stranded in mud. You stare out the window at a clean blue sky, or you stare down at a clean white page, but all you really see is the brown haze of not having an answer or not knowing what to do next. A brown dry-season night on a street in Belmont or Woodbrook when you can’t work up the enthusiasm to leave the house. The brown at the bottom of a cup of coffee, when what seemed like the morning’s fresh clarity turns out to be the same stale fog of last night.

(But “brown” is never an innocent word in this melanotic part of the world, as Chris will soon remind me.)

*

The writer flicks from one page to another to another, the images springing out at him in a random sequence that yet, gradually, begins to suggest there might be a pattern. To stop or to slow down is to risk a kind of giddy paralysis. He flicks from one page to another like a man hopping from one unsteady pile of books to another, keeping his balance only through constant motion, and only the brief ballast of his weight, descending momentarily again and again, keeps the unsteady piles of books from toppling. To stop or to slow down is to risk falling.

*

Chris talks about the drawings as “small incremental gestures”. What will these increments add up to? Sketches of each day’s ramblings that might be assembled into a map of the world? Or numerous modest, tentative attempts at answering what, from a few steps back, might look like one monumental question: What am I doing here?

What am I doing? The work of every serious artist: curious, anxious, urgent. Inventing names and symbols. Searching for patterns. Searching for sensuous forms that might communicate some private experience or apprehension of the world. A world waits to be known and felt and understood. There is never enough time.

And the special predicament of “here”: twenty-first-century Trinidad, a small, confusing post-colonial, post-everything space, “a world with two coups, murders, kidnappings, wrought iron, queen shows”. Those of us who inhabit this “here” navigating blindly, by instinct, on ground still incompletely charted. (We were the land’s before the land was ours.) And those looking from outside distracted by five hundred years of expectations about what the Caribbean is or ought to be.

Those walls pierced with breeze-blocks. Those women in Carnival bikinis and high-heeled shoes. That little metal “geometry pan” that every West Indian child carries to school, containing compass, divider, ruler. Fragments of un-epic memory, personal and cultural. But what will they look like to someone outside that culture? Are they too “local”? Are they “local” enough? Are some kinds of “local” more or less “local” than others? Who gets to name the names? Who gets to define the definitions?

“Who owns sadness? Who owns introspection?

“The question is whether I have a history or not.”

*

“Many of these islands were not supposed to be ‘societies’ to begin with, after the period of conquest and plunder. We were never supposed to be ‘individuals’ either.

“Often when I sit in my studio and make a mark on an empty piece of paper trying to imagine, dream, or figure out something, it feels odd, as if I am boldfaced to even feel I could have that right or privilege. Who am I addressing and into what conversation is it being inserted?

“The drawings are as much actions as they are objects. They record an ongoing internal struggle.”

*

A small story about hunger and survival in a small place

*

What kind of world would the images in these drawings suggest to someone who knew nothing about the artist, or about the small place he comes from? A confusing place, a sinister place, a funny place? A place where that person could imagine “real” people living, a “real” place with “real” problems”? What would that person make of the drawings’ collective title, Tropical Night? Would it sound like an ironic joke? Would he think, so they too have “night”? Would he grope back into etymology and remember that a tropic is a place where something turns?

Who is turning, who is turning into what?

*

What are the true names for these things? A small wooden bench, a distinctive triangular notch cut between its legs. A starburst shape that might be a flower or a leaf, a halo or a collar, or a setting sun. A medieval map of the Old World, continents with crinkled edges and rivers like roots or worms, writhing. Flights of hummingbirds, conspiring. Men jumping or swimming or trying to keep their balance. Monsters, sometimes one-eyed, sometimes two, cramming their mouths with human flesh. Loaves of bread. Slices of cake. The numbers one, two, three, seven. Dogs marking their territory. Feet. Cages and fences. The sea, or the horizon that hovers beyond. Women in Carnival bikinis. The silhouette of a young man, his bald head carrying absurd burdens, or filled with visions of all the above.

Of whose world is this a catalogue? Of whose history are these the chapters? Whose lexicon? Whose game? Whose fate?

*

And what, then, do these drawings “mean”? What is the statement, the ideology—the point?

What if the point is, simply, the act of drawing itself, of following these private, personal whims and speculations? Ink on paper, thoughts on the fly, in the rough? Confidence (or faith) in the final value of the process, of the act, an act like a kind of hyper-aware meditation?

“Canvas is like millennium talk, it’s like the big statement.” These drawings are like everyday talk. Is there something unexpected about the modesty and quietness and patience of the enterprise? Drawing as an end in itself, not as a means of preparing for—sketching out—rehearsing—some grand programme or position?

“The empty canvas is a territory of the Western canon, or the nationalist one. Painting implies a kind of surety, a kind of purpose for posterity. Drawing, to me, is ephemeral and immediate. I want to talk about occupying the frame with my thoughts.”

Not something to say, but a willingness to investigate what might be said? And, hence, what might not?

Annie Paul: “he has developed a form of note-taking (taking note as opposed to taking notes) using a visual stenography with which he sketches his location and state of mind.”

Like a writer opening his notebook, letting the world read those private jottings—observations, anecdotes, questions, recollections, lists of random words and phrases, half-remembered quotations, false starts—that might or might not otherwise be the raw material of some more finished work, which could more safely, more certainly, be called “literature”.

*

“I am enjoying not having to account for myself. Can I just enjoy the aesthetic, the immediate sensation? Can I have fun?”

*

The writer must start somewhere, so he starts with the simplest, most ordinary word he can think of. Anything could follow this word. The word is: “the”.

The writer stares at this word, scrawled in the upper left corner of the no longer empty sheet of paper. Anything could follow this word, but staring at it, the writer realises he doesn’t know anything.

He stares at this simple, familiar word—“the”—until it begins to look strange and unsettling. The writer wonders if anyone has ever really looked at this word before—the shapes of the letters, their darts and curves. The “t” and the “h” like cruel hooks turned this way and that. The “e” like a sickle. How would you pronounce a word like this? Why would you wish to? The writer wonders how anyone has ever been able to write this word, make those particular shapes with a pen, and then go on to write another.

Like the writer, the artist does not know where to start. The artist stares at the empty, white sheet of paper; he studies its grain, the way one corner curls slightly away from his table, the microscopic specks of dust across its surface.

The artist, like the writer, must start somewhere, so he draws a line: a simple horizontal line, in black ink, across the middle of the sheet of paper.

A line across the sheet of paper, for the writer, means either a blank space waiting to be filled, like this: ____________; or a sign for deletion, for removing something that, because the ink mark has already been made, cannot really be deleted: like this.

Either way, for the writer, the line is a mark of failure. It goes nowhere.

For the artist, the line is a line, one of the basic elements of his medium. It is a beginning. It can go anywhere. It is a horizon, beyond which all is possible.

The writer knows it is unfair to think so, and furthermore untrue, but he thinks it anyway, constantly: it is easier for the artist.

The writer wonders: What am I doing here?

*

The challenge is to calculate the amount of energy needed to spring again

*

“Artists are more concerned with who they actually are or may be than with the ‘what’ they are supposed to represent.”

*

—You could take a longer, wider metaphysical view and argue that every artist or writer comes from a small, peripheral place: the Republic of the Self, where to be a citizen is to be an exile.

—And the other way round.

*

“I am not sure what I am doing.”

*

Chris is saying: “If you just take this”—he picks up the stack of paper, say seven by seven by nine inches, holds it in the air for a moment, puts it back on the table with a gentle thud; it has weight, it casts a shadow—“if you just take that as an object, what it says is, all of these thoughts are in there.

“When you look at that, it’s just so beautiful. It’s a stack of paper, and all the mysteries that it entails.”

*

. . . on the edge between what looked infinite and what appeared to be finite or known and understood allegedly . . .

*

“There is no end in sight.”

***

Those early days: text from drawing “Immersed in Explanations”

“It feels like saying something twice….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 10 May, 2007

“I like to draw….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“There are narrative passages….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

Sending for sweetness: text from drawing “Lucky Seven”

“The texts on the drawings are written free-form….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“The word ‘literary’ could imply….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 10 May, 2007

“the imagery as it unravels….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“a mood or tone I often feel….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“shadowed space that is not between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

“A world with two coups, murders….”: C. Cozier, in Uncomfortable: The Art of Christopher Cozier (2005, video, 47:38), by Richard Fung

“The question is whether I have a history….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“Many of these islands were not supposed to be ‘societies’….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

A small story about hunger: text from drawing “Cyclops”

“Canvas is like millennium talk….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“The empty canvas is a territory of the Western canon….”: email from C. Cozier, 18 June, 2007

“he has developed a form of note-taking….”: Annie Paul, “The Enigma of Survival: Travelling Beyond the Expat Gaze”, Art Journal, Spring 2003

“I am enjoying not having to account for myself….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

The challenge is to calculate: text from drawing “Hop Skip Jump”

“Artists are more concerned….”: C. Cozier, from draft of text read in his studio, 11 June, 2007

“I am not sure what I am doing”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

“If you just take this….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

. . . on the edge between: text from drawing “Immersed in Explanations”

“There is no end in sight”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

The Tropical Night blog is a creative collaboration between Christopher Cozier and Nicholas Laughlin, evolving from the series of drawings. See more images from the series in this Flickr photoset.

Working notes: On Christopher Cozier’s Tropical Night drawings

By Nicholas Laughlin

First

published in the catalogue of Little Gestures: From the Tropical Night Series, an exhibition at the Jaffe-Friede Gallery,

Hopkins Centre, Dartmouth College, 2 October to 4 November, 2007

Those early days sitting in the water and watching the horizon and looking backwards to the edge of the island and wondering about the space in the water . . .

*

Almost one whole wall of Chris’s studio is a big wooden door that opens to the east, to the first morning light, and a view of a lawn, some small trees, the road below, and a forested ridge above. Another wall is covered by two huge drawings, from a series he worked on a few years ago. The third wall is lined with untidy bookcases, disgorging art books and catalogues, and dusty hardbound volumes of classic West Indian novels discarded by a library in Port of Spain, their spines still tattooed with Dewey decimal call-letters. On the fourth wall, dozens of evenly spaced pushpins make a sort of grid. Sometimes the grid is filled with small drawings hanging from clips. Sometimes the wall is mostly empty.

A big table sits right across the doorway. There is a strong lamp suspended above, and a tall stool pulled up alongside. On the table there are bottles of ink, tubes of paint, jars of brushes; a telephone, scraps of paper with phone numbers, names, lists; a bowl of coins from many countries, a row of ornate old-fashioned soft-drink bottles—Solo, Ju-C—and all sorts of odds and ends and strange objects, some of which may be artworks or fragments of artworks; and, on the only patch of clear surface, a stack of paper six or seven inches high.

Apart from the tall stool near the table, there are three old kitchen chairs, which came from Chris’s parents’ house in Diego Martin. There are boxes in the corners, some labelled (“Unsorted Mail”), some anonymous. There are small shoals of CDs, bits of discarded clothing—a purple sock—and what look like scraps of lumber. There are paintings and drawings in frames, stacked facing the walls. There are children’s toys, strayed from the rooms of the house above.

Several times over the last year I’ve visited the studio to look at the ongoing series of drawings Chris calls Tropical Night. Sometimes the drawings—each about nine by seven inches, on thick paper—have filled the pushpin wall. Sometimes they are stacked on the table or stool.

Say seven by seven by nine inches, the stack of paper: a solid object. It has real weight. It casts a shadow. Chris talks about exhibiting the drawings like this: piled up, face down. The longer I stare at the stack, the more it looks like a piece of minimalist sculpture, a cuboid with ridged edges stained with brown ink.

When the time comes for me to leaf through the drawings, Chris usually finds a reason to leave the studio. I turn the drawings over like pages in a book. Each time, the order has changed. Human figures, maps, birds, the sea, walls, benches, limbs, numbers. Some of the drawings have become familiar. Some are variations on ones I’ve seen before. Some are entirely new. The new drawings shift the narrative, as it were; I thought I’d put a story together, but now there are fresh meanders in the stream of consciousness. I don’t, after all, know where this is going.

*

“It feels like saying something twice, or again the following day in another conversation, and realising some connection or what the idea was really about.”

*

I am sitting in one of the kitchen chairs in the studio, sipping from a cup of milky coffee, staring at the pushpin grid on the wall in front of me, and listening to Chris. Words spiral and spool, as he plucks anecdotes from his capacious memory, pinches together recollections and observations and insights, facts from yesterday’s newspaper with fifteen-year-old gossip.

One of Chris’s favourite words is “conversation”. He uses it in every third or fourth sentence. But in my conversations with him I find I mostly listen. Partly because I’m caught up in the swirl of his words and ideas, and don’t want to interrupt. Partly because his intense and effortless verbalness leaves me feeling wordless. Images are supposed to be his medium, words mine. So why does he find it so easy to spin his phrases and lyrics, why do my own sentences feel like knots of barbed wire in my throat?

*

The writer, like the artist, works in a small room crowded with strange objects. He sits at a low, square table, painted brown. The table faces a window.

It is early morning, and the light is still soft. The writer, like the artist, sits and stares at the sheet of paper before him: empty, white. In his hand he holds a pen.

Making ink-marks on a sheet of paper: that, it has been said before, is what artists and writers have in common. But this morning the writer does not know where to start; or, rather, how.

In his hand, the very slight weight of the pen—Sanford Uni-Ball Onyx, fine point, blue ink—is a gesture both familiar and strange. The pen is both a comfort and a taunt. And the empty, white sheet of paper is a prism through which the writer peers into a dark-filled, light-filled space that, this morning, looks completely empty.

*

“I like to draw. Drawing is my handwriting, and my thought process.

“I often use the word ‘note-taking’—note-taking to me is conceptually very important. It’s a process of investigation, of speculation, of questioning. It has to do with notions of being sure and notions of being unsure. There’s a kind of instantaneity in that moment of reverie, of thinking. That’s the free space I’ve created for myself. But at the same time, the fact that these are just simple thoughts on simple pieces of paper means that to be speculative isn’t weakness. Speculative is openness. It’s a domain of possibility.

“When I make those marks, there’s a sense of being alive.”

*

The iron fence of a now-demolished colonial mansion, its palings sprouting fleur-de-lis finials. An athlete’s podium, its one-two-three steps irrefutably defining degrees of victory. A cash register with empty drawer lewdly gaping. Women in white high-heeled shoes. Men peering over walls. A man embracing nothing, embracing an empty space where something should be, the exact shape of another body. Tufts of bright green grass springing from the blackened earth of a burned hill.

Who is inside? Who is outside? Who is stepping out, or up? Who is stumbling in, or down? What happens next?

*

—Something’s worrying you about these drawings.

—Yes.

—What?

—The same thing that worries me about these notes I’m trying to write. It’s the matter of having to explain. To elucidate.

—To elucidate is to “make clear”….

—But “making clear” is the opposite of what the drawings seem to do—the prevailing murky browns and greys are like a tonal metaphor. But I also mean something else. Something like what Chris means when he asks if the work has “readability on its own merit”.

—The burden of narrative?

—No. What you might call the burden of context. The burden of history. The burden of being from a place—it’s tiresome to keep saying this, but even more tiresome that it’s true—from a small, peripheral place where individual sensibility is trapped on all sides: by ideologies, by national “culture” narratives, by stereotypes—by that whole tangle of expectations about what it means to be an artist from and in the Caribbean.

—But the subject matter of the drawings is unavoidably “from and in the Caribbean”—it’s the sometimes mundane, sometimes crazy everyday of an individual living in Port of Spain and immersed in all the elements of life in the twenty-first-century urban Caribbean—all those elements processed into what you’ve described as a visual stream of consciousness….

—Yes, but must the elements of that stream, that consciousness, be annotated for an audience outside that twenty-first-century urban Caribbean context? And in the absence of such annotations (which I’m not interested in providing), can that audience—will they—respond to lines, shapes, colours, tones, the immediate sensation, the “brown”, the mood, the mystery?

—And your notes?

—Don’t explain anything. Don’t come to any conclusion. Merely describe my own hesitant, indecisive experience of the drawings—looking at them, puzzling over them, talking to Chris about them.

—And you worry….

—Whether that is enough. Whether the notes themselves have any “readability”. If I had any talent for fiction I would write a short story instead.

*

“There are narrative passages. There are moments when I see a path, and I try to run it down.” But: “Sometimes I don’t want to prescribe the reading.”

The reading. That is my urge: to “read” these images, like a story, like a book.

Maybe it’s the “bookness” of the stack of drawings, sitting there like an unbound novel, with the patience of a book. (A book will wait five hundred years, then a reader opens it and the words unfurl fresh as flowers.)

Maybe it’s the lines of text, in Chris’s ornate scrawl, that embroider the drawings, not naming or explaining, but reaching, it seems, for their own plotlines.

Maybe it’s the many hours I’ve spent talking with Chris, or listening to him—maybe they’ve convinced me that he has something like the sensibility of a novelist, taking in and storing away every detail, penetrating into the deep psychology of things and places and people. A poet’s instinct is to pare away, a novelist’s is to pile up, pack in, fill the room of the imagination with as much furniture, as much equipment, as much apparatus as possible.

Or maybe the “book” I’m trying to read is a reference work: a dictionary, or an encyclopedia, scrutinising the world, imagining its complexities into small constituent fragments, holding each fragment up to the light, describing it from many angles, enquiring after its pronunciation, its derivation, its possible and impossible uses.

I look up and for a moment it seems the images in the drawings have taken three-dimensional form and are populating the studio. Near-invisible lines of trajectory connect object to object, and object to image on the pages in my hands. I am caught in this web, and the whole room is washed in sepia ink.

I close the “book”.

My eyes readjust and once again I see chairs, bottles, boxes, scraps of wood.

The stack of paper sits on the only patch of clear surface on the table, jostled by jars of brushes.

I am thinking: Do these drawings “rhyme”? Do they have a “rhythm”?

*

Searching for sweetness in the darkness across the sea

*

“The texts on the drawings are written free-form. Sometimes there’s spelling mistakes, grammatical mistakes, and things repeat, because the idea is a kind of associative writing, a rambling, that I then place in the context of the drawings.

“I’m never sure if they’re explanatory, or if they’re sort of parallel.”

*

I realise that the drawings cast into clearer relief a certain literary quality of Chris’s entire oeuvre. I don’t mean just that he’s a practising critic. I don’t mean just that his works on paper, even at their most cryptic, almost always have a strong sense of narrative. I don’t mean just that his groundbreaking early work, Conversations with a Shirt Jac, was in effect a soliloquy; or that his sound installations seem to play with elements of performance poetry; or that text—actual writing, the physical shapes of words—recurs through his drawings. I mean—and I’m trying to understand—something about his mode of thought, the way Chris experiences and understands the world. His mode of thought seems essentially that of a writer. He has what I think of as a writer’s intense self-consciousness, a writer’s obsession with translating the world into words to keep the world from disappearing (as it ultimately must). Drawing is his note-taking, he says, but I suspect he also has that voice in his head that never stops detailing and describing, converting sensory facts into words and those words into sentences, so that each day is an epic novel of the mundane that will never get written, and memory is a series of inaccurately recalled quotations, and these drawings are snapshots from a stream of consciousness, from an unresolved state of being.

An autobiography composed from metaphors.

A visual dream-diary. Of waking dreams.

*

There is a kind of bibliophile’s parlour game in which you arrange books on a shelf so that the sequence of titles on their spines tells a story.

You might do something similar with the titles of the individual drawings in the Tropical Night series.

Feathered Bat Descending. In the Dance. Hop Skip Jump. Jump Up. Shot Call. Flight.

Coming and Going. Immersed in Explanations. Submerged.

Oxford Journey. Castaway. New World. Making Progress.

A Next Day. Sitting Here Watching. Open Seas. Day In, Day Out.

After the Fire. Crown. Thorns. Bird Stress. Air. The Hills. That Tree. The Hunger.

Another kind of narrative. Another way, perhaps, of not seeing the thing at hand, the marks on the piece of paper before me.

*

“The word ‘literary’ could imply or require a narrative pursuit, and that may limit me or demand a purpose or some kind of accountability. I do not really want to have a way through this, or an idea of a way. I feel adrift, a bit lost, and I am looking for and at signs. I do not want to frustrate the viewer. I am searching for empathy.”

*

A white wall covered with a grid of evenly spaced pushpins is a map waiting to be drawn.

A blank sheet of paper is an airless room waiting for a conversation to start.

*

When Chris first gave me scans of some of the drawings, I put them in a folder on my desktop called “Brown Drawings”. Maybe he used this term casually in some early conversation. Maybe it was the first thing that came to mind when I made the folder, more than a year ago—the label that my semi-conscious mind grabbed at to distinguish these from his earlier work.

Many of the drawings are literally “brown”, composed largely in washes of sepia ink. Some are not. This is obvious. This is the artist’s prerogative of medium. It is also obvious that the “brown” is, more meaningfully, a mood. The dark brown of dried blood—

“the imagery as it

unravels always seems to be in this dark, this dark murky space in

which we are searching for light”

—or the weary brown of an old photograph, but not the kind of photo that inspires nostalgia, like an old black-and-white snapshot of a Carnival costume from the 60s or 70s, and looking at it you feel the dust and hot sun of that moment, the weight of the costume and the stickiness and the head-pounding noise, and you’re glad you’re not there; it might even be a moment from your own past that you’re glad you don’t have to relive. Or just a meteorological brown—

“a mood or tone I

often feel on a dreary day, waiting for a taxi before it rains or going

to some kind of daily routine”

—a tone of spirit familiar to anyone who grew up in the tropics, a brown found only in this climate, like a film of dust over the bright blues and greens and yellows that are supposed to be the exemplary colours of the tropical landscape; the gloom of that “shadowed space that is not between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. with intermittent clouds.”

The murky brown of a situation or a frame of mind when the silt of too many memories and expectations leaves your thoughts stranded in mud. You stare out the window at a clean blue sky, or you stare down at a clean white page, but all you really see is the brown haze of not having an answer or not knowing what to do next. A brown dry-season night on a street in Belmont or Woodbrook when you can’t work up the enthusiasm to leave the house. The brown at the bottom of a cup of coffee, when what seemed like the morning’s fresh clarity turns out to be the same stale fog of last night.

(But “brown” is never an innocent word in this melanotic part of the world, as Chris will soon remind me.)

*

The writer flicks from one page to another to another, the images springing out at him in a random sequence that yet, gradually, begins to suggest there might be a pattern. To stop or to slow down is to risk a kind of giddy paralysis. He flicks from one page to another like a man hopping from one unsteady pile of books to another, keeping his balance only through constant motion, and only the brief ballast of his weight, descending momentarily again and again, keeps the unsteady piles of books from toppling. To stop or to slow down is to risk falling.

*

Chris talks about the drawings as “small incremental gestures”. What will these increments add up to? Sketches of each day’s ramblings that might be assembled into a map of the world? Or numerous modest, tentative attempts at answering what, from a few steps back, might look like one monumental question: What am I doing here?

What am I doing? The work of every serious artist: curious, anxious, urgent. Inventing names and symbols. Searching for patterns. Searching for sensuous forms that might communicate some private experience or apprehension of the world. A world waits to be known and felt and understood. There is never enough time.

And the special predicament of “here”: twenty-first-century Trinidad, a small, confusing post-colonial, post-everything space, “a world with two coups, murders, kidnappings, wrought iron, queen shows”. Those of us who inhabit this “here” navigating blindly, by instinct, on ground still incompletely charted. (We were the land’s before the land was ours.) And those looking from outside distracted by five hundred years of expectations about what the Caribbean is or ought to be.

Those walls pierced with breeze-blocks. Those women in Carnival bikinis and high-heeled shoes. That little metal “geometry pan” that every West Indian child carries to school, containing compass, divider, ruler. Fragments of un-epic memory, personal and cultural. But what will they look like to someone outside that culture? Are they too “local”? Are they “local” enough? Are some kinds of “local” more or less “local” than others? Who gets to name the names? Who gets to define the definitions?

“Who owns sadness? Who owns introspection?

“The question is whether I have a history or not.”

*

“Many of these islands were not supposed to be ‘societies’ to begin with, after the period of conquest and plunder. We were never supposed to be ‘individuals’ either.

“Often when I sit in my studio and make a mark on an empty piece of paper trying to imagine, dream, or figure out something, it feels odd, as if I am boldfaced to even feel I could have that right or privilege. Who am I addressing and into what conversation is it being inserted?

“The drawings are as much actions as they are objects. They record an ongoing internal struggle.”

*

A small story about hunger and survival in a small place

*

What kind of world would the images in these drawings suggest to someone who knew nothing about the artist, or about the small place he comes from? A confusing place, a sinister place, a funny place? A place where that person could imagine “real” people living, a “real” place with “real” problems”? What would that person make of the drawings’ collective title, Tropical Night? Would it sound like an ironic joke? Would he think, so they too have “night”? Would he grope back into etymology and remember that a tropic is a place where something turns?

Who is turning, who is turning into what?

*

What are the true names for these things? A small wooden bench, a distinctive triangular notch cut between its legs. A starburst shape that might be a flower or a leaf, a halo or a collar, or a setting sun. A medieval map of the Old World, continents with crinkled edges and rivers like roots or worms, writhing. Flights of hummingbirds, conspiring. Men jumping or swimming or trying to keep their balance. Monsters, sometimes one-eyed, sometimes two, cramming their mouths with human flesh. Loaves of bread. Slices of cake. The numbers one, two, three, seven. Dogs marking their territory. Feet. Cages and fences. The sea, or the horizon that hovers beyond. Women in Carnival bikinis. The silhouette of a young man, his bald head carrying absurd burdens, or filled with visions of all the above.

Of whose world is this a catalogue? Of whose history are these the chapters? Whose lexicon? Whose game? Whose fate?

*

And what, then, do these drawings “mean”? What is the statement, the ideology—the point?

What if the point is, simply, the act of drawing itself, of following these private, personal whims and speculations? Ink on paper, thoughts on the fly, in the rough? Confidence (or faith) in the final value of the process, of the act, an act like a kind of hyper-aware meditation?

“Canvas is like millennium talk, it’s like the big statement.” These drawings are like everyday talk. Is there something unexpected about the modesty and quietness and patience of the enterprise? Drawing as an end in itself, not as a means of preparing for—sketching out—rehearsing—some grand programme or position?

“The empty canvas is a territory of the Western canon, or the nationalist one. Painting implies a kind of surety, a kind of purpose for posterity. Drawing, to me, is ephemeral and immediate. I want to talk about occupying the frame with my thoughts.”

Not something to say, but a willingness to investigate what might be said? And, hence, what might not?

Annie Paul: “he has developed a form of note-taking (taking note as opposed to taking notes) using a visual stenography with which he sketches his location and state of mind.”

Like a writer opening his notebook, letting the world read those private jottings—observations, anecdotes, questions, recollections, lists of random words and phrases, half-remembered quotations, false starts—that might or might not otherwise be the raw material of some more finished work, which could more safely, more certainly, be called “literature”.

*

“I am enjoying not having to account for myself. Can I just enjoy the aesthetic, the immediate sensation? Can I have fun?”

*

The writer must start somewhere, so he starts with the simplest, most ordinary word he can think of. Anything could follow this word. The word is: “the”.

The writer stares at this word, scrawled in the upper left corner of the no longer empty sheet of paper. Anything could follow this word, but staring at it, the writer realises he doesn’t know anything.

He stares at this simple, familiar word—“the”—until it begins to look strange and unsettling. The writer wonders if anyone has ever really looked at this word before—the shapes of the letters, their darts and curves. The “t” and the “h” like cruel hooks turned this way and that. The “e” like a sickle. How would you pronounce a word like this? Why would you wish to? The writer wonders how anyone has ever been able to write this word, make those particular shapes with a pen, and then go on to write another.

Like the writer, the artist does not know where to start. The artist stares at the empty, white sheet of paper; he studies its grain, the way one corner curls slightly away from his table, the microscopic specks of dust across its surface.

The artist, like the writer, must start somewhere, so he draws a line: a simple horizontal line, in black ink, across the middle of the sheet of paper.

A line across the sheet of paper, for the writer, means either a blank space waiting to be filled, like this: ____________; or a sign for deletion, for removing something that, because the ink mark has already been made, cannot really be deleted: like this.

Either way, for the writer, the line is a mark of failure. It goes nowhere.

For the artist, the line is a line, one of the basic elements of his medium. It is a beginning. It can go anywhere. It is a horizon, beyond which all is possible.

The writer knows it is unfair to think so, and furthermore untrue, but he thinks it anyway, constantly: it is easier for the artist.

The writer wonders: What am I doing here?

*

The challenge is to calculate the amount of energy needed to spring again

*

“Artists are more concerned with who they actually are or may be than with the ‘what’ they are supposed to represent.”

*

—You could take a longer, wider metaphysical view and argue that every artist or writer comes from a small, peripheral place: the Republic of the Self, where to be a citizen is to be an exile.

—And the other way round.

*

“I am not sure what I am doing.”

*

Chris is saying: “If you just take this”—he picks up the stack of paper, say seven by seven by nine inches, holds it in the air for a moment, puts it back on the table with a gentle thud; it has weight, it casts a shadow—“if you just take that as an object, what it says is, all of these thoughts are in there.

“When you look at that, it’s just so beautiful. It’s a stack of paper, and all the mysteries that it entails.”

*

. . . on the edge between what looked infinite and what appeared to be finite or known and understood allegedly . . .

*

“There is no end in sight.”

***

Those early days: text from drawing “Immersed in Explanations”

“It feels like saying something twice….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 10 May, 2007

“I like to draw….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“There are narrative passages….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

Sending for sweetness: text from drawing “Lucky Seven”

“The texts on the drawings are written free-form….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“The word ‘literary’ could imply….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 10 May, 2007

“the imagery as it unravels….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“a mood or tone I often feel….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“shadowed space that is not between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

“A world with two coups, murders….”: C. Cozier, in Uncomfortable: The Art of Christopher Cozier (2005, video, 47:38), by Richard Fung

“The question is whether I have a history….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“Many of these islands were not supposed to be ‘societies’….”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

A small story about hunger: text from drawing “Cyclops”

“Canvas is like millennium talk….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

“The empty canvas is a territory of the Western canon….”: email from C. Cozier, 18 June, 2007

“he has developed a form of note-taking….”: Annie Paul, “The Enigma of Survival: Travelling Beyond the Expat Gaze”, Art Journal, Spring 2003

“I am enjoying not having to account for myself….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

The challenge is to calculate: text from drawing “Hop Skip Jump”

“Artists are more concerned….”: C. Cozier, from draft of text read in his studio, 11 June, 2007

“I am not sure what I am doing”: C. Cozier, Tropical Night blog, 4 May, 2007

“If you just take this….”: conversation with C. Cozier, 22 April, 2006

. . . on the edge between: text from drawing “Immersed in Explanations”

“There is no end in sight”: conversation with C. Cozier, 25 April, 2007

The Tropical Night blog is a creative collaboration between Christopher Cozier and Nicholas Laughlin, evolving from the series of drawings. See more images from the series in this Flickr photoset.